After a visit to the Saatchi gallery last weekend put me in drawing-art-and-music-parallels mode, I got thinking about the fact that much of what’s popular and “cool” in today’s UK/US music scene is unabashedly impressionistic. Form and theme are present but blurred, lyrics often part-way indecipherable, samples topped, tailed and laden with effects. Our music libraries and gig diaries are full with hazy impressions of jazz, pop, guitar and dance music from the past hundred years.

In Taschen’s Impressionism, the late Ingo F. Walther writes:

“To paint in an Impressionistic way meant representing a seen, given reality as it appeared to the eye.. The Impressionists were particularly interested in dynamic aspects of the real, in anything that spoke of speedy flux. Indeed, the sense of change and movement was crucial – including the change and movement of light and colour.”

He goes on to suggest why it found such popularity as a style:

“..the relativity of the image, and its open form, prompted those who looked at them to look and feel for themselves in new ways, and in so doing to complete the visual image and message. The individual picture was no longer an authoritative, incontestably valid source of instruction..”

This description would seem to fit a good deal of what’s been pushing our music blog buttons for the past few years (with no sign of a let-up yet). Of course Impressionism in music began in the late 19th-century, but the heavy pedal, merging tonal colours and experimental articulation of say, Debussy, has strong parallels with the dreamy reverb, impastoed layers and shifting rhythms of Clams Casino‘s Numb (above). “Short, thick strokes of paint are used to quickly capture the essence of the subject, rather than its details” says Wiki. Our instruments/materials may have evolved, but the kind of timbre we’re aiming for remains surprisingly constant.

What can you determine from this track? There’s definitely a rolling, hip-hop-like beat; there’s someone singing – gender and words not clear; there’s some kind of wind instrument on the riff (maybe a sax?); it’s in a minor key; sounds are being played in reverse; it’s made using mainly electronic instruments.

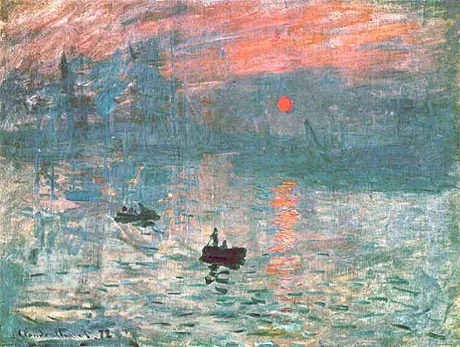

Similarly, without prior knowledge, what can we determine from the painting? It’s definitely a scene of boats on water; it’s either sunrise or sunset; there’s a suggestion of a harbour, but only that; it’s made using oil on canvas. What story are we being told here? It’s not clear, so we make one up for ourselves. Impressionist aesthetics leave ample room for creativity.

Only now, thanks to the widespread accessibility of music software (ie. boundary-blurring effects), is our mass/popular music appreciation enjoying the sort of freedom introduced by visual artists two centuries ago. Those who consider the sexuality of R&B floor-fillers or the claustrophobia of lovesick pop ballads to be too literal an association can, thankfully, bask in the comparative vagueness of Shlohmo, Burial, and Flying Lotus.